What is in a number?

This May, I was seeing the number four everywhere. The ‘fourth’ (a Star Wars reference for the uninitiated) may not have been with me but it definitely was with the Twitterati. India had apparently surpassed Japan to become the fourth largest economy. Given the context of the recently concluded Operation Sindoor, a comparison to the Pakistani economy seemed deserved in some quarters. Amitabh Kant, India’s G20 Sherpa, didn’t fail to point out that the economy of Maharashtra alone was bigger than that of Pakistan.

But what is in a number truly?

At the onset, one is obligated to point out that the GDP numbers of the IMF quoted by the NITI Aayog are estimates for financial year 2026. Though I personally think that speculation should be left to stockbrokers, making claims just two months into the financial year may not be fitting for the government’s top think tank.

To quote Mark Twain, “There are lies, damned lies, and statistics”. If one undertook a truer analysis of the Indian economy, the country is the third largest by GDP by Purchasing Power Parity (PPP). In fact, it has been so since 2009. There was a sharp increase in the rate of GDP (PPP) since 2009, which became steeper in 2020. Then again, what is in a number?

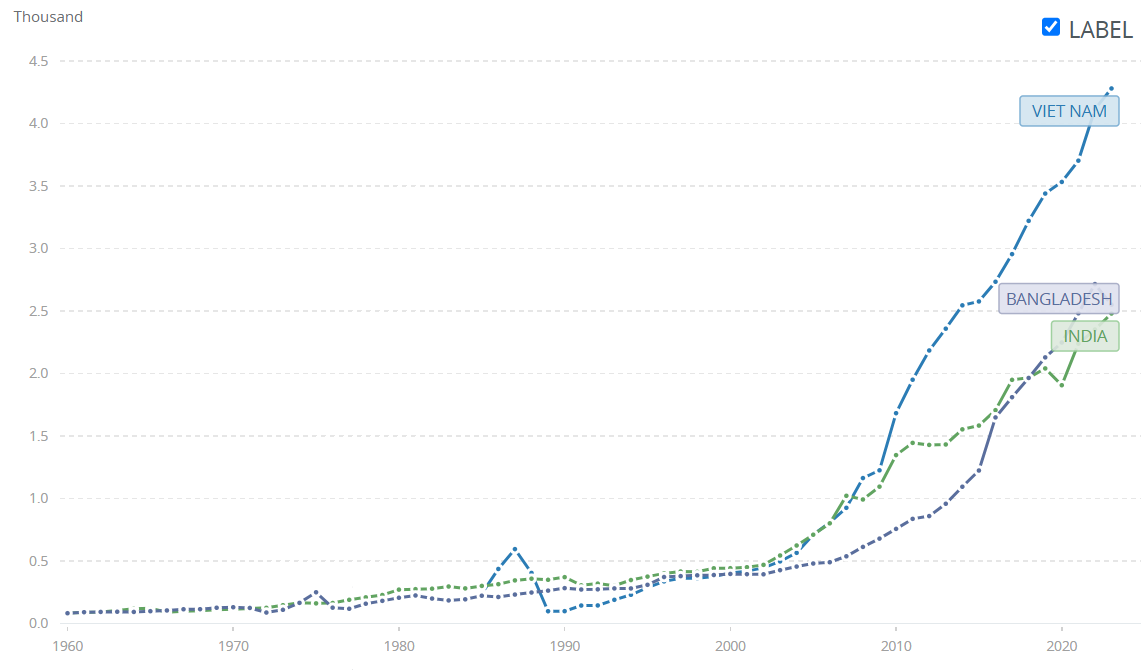

Beyond the neighbourly calumny, a comparison with economic competitors reveals a different image. India’s economic competitors (we listed this in a previous blog) have had ‘better numbers’. Despite 50 years of conflict that reduced the country to rubble, Vietnam overtook India in GDP per capita terms in 2005. According to the latest estimates, Vietnam’s household income was nearly 35% higher than those of Indian household income. Bangladesh, another one of India’s economic competitors, overtook India in terms of GDP per capita in 2018.

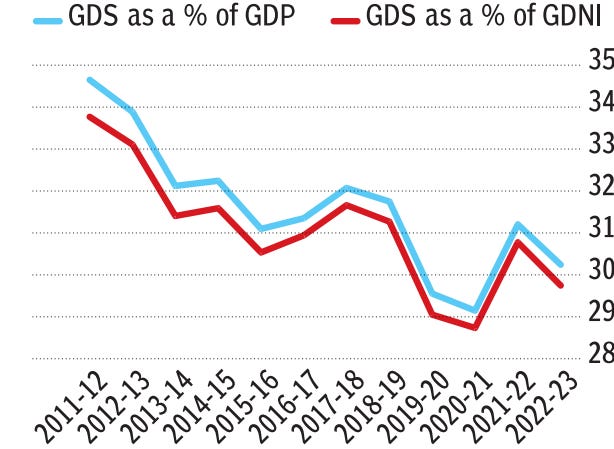

Numbers and their authors often have an odd sense of humour. The CRISIL intelligence report pointed out India’s saving rate of 29% was above the global average and reflected improved income levels. They missed mentioning that this was also the lowest rate in 40 years. Glass half empty? Apparently not. Glass half full. Falling interest rates have given way to riskier investment alternatives. Between 2020 and 2023, household investments in equities and mutual funds nearly increased from ₹1.02 trillion to ₹2.02 trillion.

Further, in the previous financial year (2024-2025), the net foreign direct investment (FDI) into India fell by 96% from $10.1 billion in the previous year to $0.4 billion in FY25. The Reserve Bank of India, though, saw this as a “sign of a mature market”. With global uncertainty as high as 82%, what do these outflows really mean? It cannot be said for sure. While Singapore, Mauritius, and the United States accounted for a majority of the outflow, they also account for the majority of the inflow—read as tax avoidance.

Being the fourth largest economy may, unlike the jubilation on X, require a muted introspection. The Human Development Index, the Corruption Perception Index, the World Press Freedom Index, and especially Rishabh Pant’s stats are a few other numbers that require introspection.